I have just visited Sebastião Salgado’s ‘Genesis’ exhibition at the National History Museum, London and wanted to share my reflections.

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/visit-us/whats-on/temporary-exhibitions/salgado-genesis/

Born in Brazil, Sebastiao Salgado qualified with a doctorate in economics before his transition to photography in 1973. Today Salgado is a world renowned documentary photographer, with an international reputation for his photography essays such as Other Americas, Migrations and Workers. His images are always taken in black and white (he believes colour is a distraction) and cover themes such as global industrialisation, to the displacement of rural communities and the rapid demise of indigenous tribes. The Genesis exhibition involved an eight year journey for Salgado with the aim of recording the relationship beween people and the planet. Is it an amazing documentation of the environment? As a visual observation of humanity and natural landscape, in scale Salgado’s lens is unrivalled. However, his critics, argue his photography often exoticises his subjects. Judge for yourself below with a small example of my favourite Salgado images and accompanying text taken from the current Genesis exhibition.

“I have named this project GENESIS because my aim is to return to the beginnings of our planet: to the air, water and the fire that gave birth to life, to the animal species that have resisted domestication, to the remote tribes whose ‘primitive’ way of life is still untouched, to the existing examples of the earliest forms of human settlement and organization. A potential path towards humanity’s rediscovery of itself. So many times I’ve photographed stories that show the degradation of the planet, I thought the only way to give us an incentive, to bring hope, is to show the pictures of the pristine planet – to see the innocence. And then we can understand what we must preserve.”

Sebastião Salgado

Main Photograph above: In the Upper Xingu region of Brazil’s Mato Grosso state, a group of Waura fish in the Piulaga Lake near their village. This region is home to an ethnically diverse population, with the 2,500 inhabitants of 13 villages speaking languages with distinct Carib, Tupi and Arawak roots. The Waura occupy different territories and preserve their own cultural identities, but all live in peace. Many of Salgado’s images exude a peaceful sense of calm, and if you listen very carefully you can almost hear the paddle gently gliding through the water.

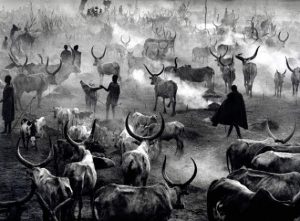

The camp is most active at the end of the day when the herd of cattle is back for the night.

Piles of white, smoky burning cow dung keep the insects away.

2,400 km long, the JuruaÌ River is one of the Amazon’s longest tributaries. It rises in Peruâs Ucalayi Highlands and is navigable for 1,800 km before it joins the SolimoÌes River. But once it enters the flat, forested lowlands known as the Amazon depression to the west of Manaus, it wiggles like a worm, curving to the left and right in order to advance barely a kilometre. Even traveling downstream, boat skippers need immense patience.

The Mursi and the Surma women are the last remaining indigenous group in the world to wear lip plates. The plate is a form of body modification inserted by the girls mother or close kin 6-12 months prior to marriage, aged 15-18 years. Academic research suggests this ritual is associated with female beauty, strength, self esteem and symbolic pride rather than the Mursi’s presupposed concept of bride wealth. See below for further ethnographic details. http://www.mursi.org/introducing-the-mursi/lip-plates

This is another one of my favourite Salgado images of the whole Genesis exhibition. It is an intriguing and charmingly innocent photograph of ten naked Zo’e adolescent girls and women in various juxtapositions; happliy relaxing, standing, sitting and reclining together in a gendered space of woven palm leaves. Many appear to be going through a collective cleaning ritual of their own and each others bodies completely oblivious to the lens of Salgado’s male gaze. (Or maybe the composition was staged?). The curiousity of this image stems from the white protruding cones called poturu, a wooden plug piercing the bottom lip of all Z’oe members as a form of tribal identity. Note how strings are also symbolically tied around some of the womens’ upper calves and ankles which is seen as a sign of female strength and beauty.

The rural indigenous Zo’e population total approximately 400 people in the state of Para, Northern Brazil, one of the last, largely unexplored rainforests in the world. The Zo’e are part of the Tupi linguistic group which is an endangered indigenous language, and in 2007 all were monolingual. According to Jean-Pierre Dutilleux the marriage rituals of the Zo’e are complex. Many women practice polyandry and one or more husbands may be “learning husbands” where young men learn how to be good spouses, in exchange for hunting for the rest of the family. Interesting…

As an anthropologist, I always find it interesting to listen to peoples exhibition attidudes about human behaviour. We are all culturally conditioned by our environment, and if Salgado has inspired you to pick up your camera and travel the globe; don’t forget to explore the Genesis exhibition at the Natural History Museum before you click the shutter on the rich diversity our planet offers.

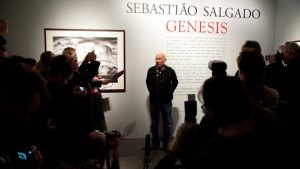

A wonderful moment when I am actually in conversation with the master Sebastio Salgao himself. I am humbly attempting to discuss the relationship between anthropology and photography, and he’s actually listening!!

Recent Comments