“After the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, still alone, more faithful but with more vitality…the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls ready to remind us, waiting and hoping for their moment, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unfaltering, in the tiny almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection”

( Proust: Remembrance of Things Past: 1970: 36)

Smell is strongly related to emotion, and according to the ‘Proustian phenomena’ in contrast to the other four senses, namely vision, sound, touch, and taste, odour memory has the greatest ability to transport us back to our distant past. This theory and quote from the French writer Proust, recalls long forgotten childhood memories after smelling a tea soaked Madeline biscuit. The world of odours and the perception of smell is recognised by olfactory scientists as one of the most complex of the five senses. Smell is often related to taste and pleasant aromas or contamination in food, but equally physical arousal or disease of the body. Smell is established through social conditioning and like emotion, this varies cross culturally, with different genders and generations. However, research is still riddled with scientific mystery, but if you want to know more I suggest the following publication for an olfactory starter.

“The Smell Cultural Reader” (2006) by Jim Drobnick, Sensory Formations.

As an academic pathway within my Talking Streets projects, I was fortunate to engage in some interesting anthropology research on the cultural mapping and meaning of smell amongst the streets of the former Bermondsey Tanneries in South London. One of the strongest leather tanning smells I have ever previously encountered is linked to one of my favourite places, namely the famous souks markets of Fez in Morocco; and despite my journey several years ago I can still vividly recall the smell. So Proust was right! As a Unesco world heritage site, Fez is a wonderful cultural example of a traditional 9th century human settlement. Established in the medina, the old Moroccan town contains beautiful Islamic mosques, palaces, fountains and colonial architectural remnants. Consequently, the famous Fez leather tanneries are the oldest in the world, and an unforgettable olfactory experience for every visitor. As you walk through the colourful souk, you encounter a rich, tangible, architectural history, as the decorative Moroccan houses purposely built and lined along the dark, narrow alleyways are crammed with local street sellers. For some people, this subjective experience of space is rather oppressive; and interesting discussions relating to wayfinding in the built environment (Ingold: 2000) and how to navigate and spatially orientate from a to b spring to mind in this intricate, vernacular maze. Particularly in the twisting ‘Sbaa Louyate’ the ‘Street with Seven Turns!’ (not to be confused with ‘Pasaje de Siete Vueltas’, ‘passage of seven turns’, and Calle Quijarro, the narrow colonial streets in Potosi, the Bolivian silver mining town). However, as with all intense odours, you smell the tanneries before you see them, as the dense smell lingers heavily, almost tangibly in the air, often up to 40 degrees under the burning North African sun.

Moroccan leather skins from sheep and goat hides are cleaned in stone circular vats using a traditional acidic format, rubbed with pigeon dung or excrement to remove animal hair and make the material supple. The leather is then re-soaked in vats containing coloured liquid dyes and pounded by the leather tanners in the same traditional way today as in previous centuries, using their bare hands, arms and feet. The leather is eventually dried on the souk roofs and cut into handbags, slippers and jackets for local and tourist consumption. To observe this leather tannery process is an assault on the senses, to which the tanners have gradually desensitised. Visually, through the coloured dyes but primarily due to the penetrating smell, that is a combination of decaying skins, urine and dung. Tourists are given fresh mint leaves to inhale or roll into a ball to insert the nostrils. The initial smell works for up to 10 mins before both leaf and people start to fade. Nevertheless, this experience confirmed that the transmission of Moroccan cultural heritage is preserved, but the main threat is an increased population within the fragile infrastructure of the medina. I also discovered our smell vocabulary is curiously limited, particularly when describing this smell or any smell to someone that hasn’t smelt that smell from the same or a different culture!

Bermondsey Smell Scape Research

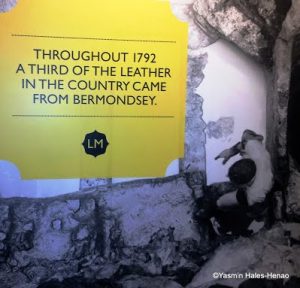

From an anthropological context, the Fez souk provided a useful ethnographic study and first hand understanding of the cross cultural meaning of smell, and secondly, a comparison of the similarities and differences from production to consumption of the leather tannery process. More locally the South London neighbourhoods of Bermondsey are associated with various regeneration projects, so this qualitative fieldwork initially aims to spatially map the history of these changing streetscapes and explore the former commercial role of the leather tanneries by interviewing local employees.

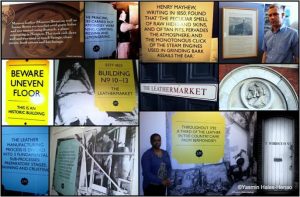

Bermondsey research theory and methods of space, place and the built environment are developed around historical photographs complimented by a final oral and visual project. Simon aims to further develop an independent anthropological framework by listening to residents’ stories and recording oral histories that link family and childhood memories to a shared intangible heritage, and experience Bermondsey past smells in the present.

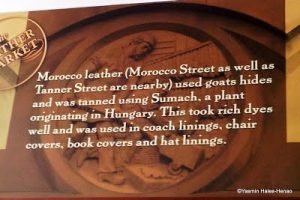

Leather market plaque highlighting cultural and geographic link between Moroccan and Bermondsey streetscapes, tanning process and products.

How does a building, street or neighbourhood evoke memories and particular feelings through their association with particular smells?

“The relationship between smell and memory is a fascinating and powerful one, engaging the senses and emotions in a way that can bring the built environment to life. The Bermondsey Street smell-mapping project is focused on the area’s links with the former tannery industry. Building on my post graduate ethnographic research interests at University College London, in 2012, I have been developing further academic areas of exploration with the guidance of Social Anthropologist Yasmin Hales Mphil. This has provided an exciting opportunity to explore and develop the concept of ‘smell-mapping’ in a rapidly changing urban environment and to engage in a cross-cultural, inter- generational examination of Bermondsey’s cultural heritage. We are now continuing this research project and I am looking forward to further fieldwork interviews about smell and space with current and former Bermondsey residents and workers very soon”. Simon Finnis (MA) UCL April 2015.

From leather tanneries to musty books, your favourite food and perfume, there is nothing quite like the sense of smell. Research into anthropology of the senses is still at the cutting edge, so I am looking forward to the Proustian affect of more tea soaked Bermondsey madeline biscuits in the future.

For further reference, the London Bubble Company is a community theatre organisation in Southwark, South London that is producing some intergenerational theatre performances of the oral histories collected through a project called from Docks to Desktops. Part of the community research on the “Whiffs and Pongs” of Bermondsey involved talking to local residents that formerly worked in the South London area on how changes in employment affected change in the community life. Bermondsey factories included Peak Freans biscuits, Hartleys Jam factories and of course the Leather Tanneries. All of these smells, both fragrant and repugnant were reproduced in order to collect some lovely amusing stories and collective memories. For further details and to view the Creativity and Wellbeing Bubble scratch performance in June 2013, click below.

http://www.londonbubble.org.uk/page/whiffs-and-pongs-of-bermondsey/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pVtXPtISfww

“I know every book of mine by its smell,

and I have but to put my nose between the pages to be reminded of all sorts of things”

George Robert Gissing: English Novelist

Copyright © 2015 Yasmin-Hales Henao . All Rights Reserved.

Recent Comments