January 2016 started with the delivery of my Talking Streets social anthropology research methods course, located at the British Library, to a small, independent group of former undergraduate and post graduate students from Birkbeck and UCL, London University. The aim was to explore the theoretical experience and expression of space and place and devise appropriate research methodology to investigate the term Talking Streets. These ethnographic case studies illustrated how space is mapped and appropriated by contemporary street artists in the multicultural community of Bricklane, ‘Banglatown’ and Shoreditch in East London. After building a theoretical framework based on anthropology and cultural geography texts including Decertau’s (1984) Spatial tactics and Lefebvre’s Rhythmanalysis (2004), we navigated through the vibrant ethnographic streetscapes to explore the world of London’s contemporary street and graffiti artists.

Anthropology research was conducted with a graffiti writer on a personal guided tour around Shoreditch followed by a separate interview which contextualised the similarities and differences between writing on walls, street surfaces and tagging by established artists such as Banksy, Rhoa, Stik, Swoon, Alice and Ludvic. Students’ interdisciplinary research questions linked to interests exploring the meaning of space, street art and in what way the built environment determines behaviour. Why did artists map and choose certain streets, decorate particular walls with particular motifs and how did this impact upon community space? As the artists and local residents became potential informants, a student understanding of the different styles of research questions, issues of language translation and interpretation provided excellent practice in interviewing techniques and an integral aspect of anthropology research training in London.

Kelly’s fieldwork interest in a female street artist resulted in an alternative gendered perspective. “I instantly loved the draftsmanship and the soft palette that Alice Pasquini has captured in her work of a young boy which reveals a finer female sensitivity in contrast to her fellow male street artists. My question to Alice would simply be ’how do you feel as a female street artist hanging around in dark alleyways, as running from the police and climbing over barbed wire can’t be that much fun can it?’ ”. Art has no boundaries, and the greatest canvas to see your work, whether male or female is the street. However, the tough face of stereotypical male artists now appears to be changing influenced by the rapid rise of young, urban, female street and graffiti artists on a global level.

Simon was interested in spatial mapping and the relationship of people to their surroundings. His performative research methodology questioned how the streets are used as a site for complex interactions that come alive at certain times of the day. “My research considers the nature of the streets, the influences of architecture, the types of surfaces and spaces that people prefer to work with and the influence of the area’s ‘alternative’ art scene. I propose to explore how an absence of control creates a form of ‘seepage’ that allows people to manipulate public space in various ways, allowing for a greater variety of self-expression than in tightly regulated spaces. Graffiti and ‘Street Art’ are examples of this tendency and transgression in an urban context”

Beth was interested in exploring the ancestral lines tracks and traces (Ingold 2004) produced by multicultural residents of Muslim, Jewish and Hugonaught descent in Bricklane from 16th-21st century: “The lines of our heritage and memory are made up of the tracks and traces of our lives, which cover the surface of everyday human existence. The surface can be taken as our heritage, as through time we leave traces of who we were, who we are now and who we will be. What cultural marks do we leave through the traces of our lives today?” Additional anthropology research methodologies relating to cultural memory and shared heritage that shapes the environment for users included, an investigation of recording oral histories supported by historical and contemporary photographs

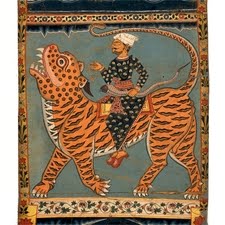

As a Bengali, Apu was interested in the notable absence of Bengali street art and lack of visible Bengali artists in Bricklane in contrast to their rich cultural artistic expression in India. “During this ethnographic project my research suggests there is not a single, visual example of either graffiti or street art on any wall or street in Shoreditch by the Asian artists. I found this curious, as the meaning and attraction of this contemporary place is cultivated by the local Bengali community and tourists as the ‘Bengali Curry Mile’, but all the images were produced by Western and European artists? How do Bengali’s express their feelings and nostalgia for their homeland in a space increasingly full of urban designs? Where are our cultural signs and symbols?”

The absence of street artists from the Bengali and Bangladeshi ethnic communities in Bricklane raises an interesting point for the Talking Streets, as walls speak in different ways in different cultures. In West Bengal the indigenous story telling tradition of rural Patua Scroll painters has a long historical and artistic tradition, and in turn the 19thc street artists in Kolkata were equally associated with popular Kalighat paintings. Education and entertainment are both forms of street art that form part of Indias’ shared national heritage. Today Bengali urban street art in is more often aligned with dominant political street campaigns and election banners within urban cities. For political graffiti artists, writing is their livelihood but mural art is often banned as a way to maintain cleansing and spatially sanitising the public arena. “It is a desire to rid the space of citizenship of all the noise, smell and gaudiness of a publicly mobilised plebeian culture that is now being seen as both an impediment to and an embarrassment for an India seeking to be become a world power,”. Sociologist Partha Chatterjee.

To what extent, the dying tradition of Bengali artistic heritage will be transmitted in any shape or form by residents in Bricklane will provide an interesting future study. The present global artists provide a recognised credibility, vibrancy and increasing tourism to this urban street space. However, there are obvious semantic messages as well as hidden graffiti agendas and occasionally these visual images also provoke religious beliefs and cultural identities resulting in mural rows. This includes the councils cover up of the ‘Crane of Brick Lane’ by Rhoa, my favourite Belgian artist, due to his sheer street scale, skill and risk, and more recently an offensive new mural that has caused a frenzy of spatial sanitising amongst political commenter’s in Tower Hamlets. http://trialbyjeory.wordpress.com/2012/09/29/a-new-mural-row-in-brick-lane/

Overall this alternative and exciting discovery of Street Art in Bricklane, East London formed an invaluable fieldwork experience for all students. These rich ethnographic case studies demonstrate the importance of student first-hand experience of anthropology field work at home, and how the meaning of graffiti space and place is successfully used as a research tool for qualitative data collection on tangible and intangible cultural heritage.

“Yasmin, I really enjoyed the way you have merged all our student thoughts and points of view into your blog of the Bricklane and Graffiti Artists. This Space and Place course and fieldwork for me was truly revealing about the mixed East End communities of London. The vibrancy, variety, innovation and cultural messages drawn, tagged or stencilled, down the back alleys, walls and open streets around Shoreditch was great and I learnt alot. I visited Delhi soon after my day with graffiti artists in London and saw for the first time ever, the amount of gritty street art now peppering its way through similar Indian alley walls and open streets of the city. Indian men and women now have a lot to say about their culture and are rapidly posting on walls. Thank you Yasmin, for an eye opening and quite heart searching day!” Beth Jordan: April 2016

“Talking Streets is an interesting and exciting concept devised through the academic research of my tutor Yasmin Hales in Pondicherry, South India, that brings together the meanings and layers of urban life through a multi-cultural approach to contemporary living and everyday experiences in the city. I have particularly enjoyed applying the theories and methodology associated with space and place that Yasmin developed with fellow students to fieldwork in a vibrant and interesting part of London, namely Brick Lane and Shoreditch. The research into Street Art and Graffiti was fascinating, uncovering a subject I had little prior knowledge of, as it revealed how people interact with, and perform in, urban spaces enabling the streets to talk in a diverse and complex artistic way” Simon Finnis April 2016

“The Talking Streets of Bricklane was an invaluable experience and we learnt a lot by slowly linking the pieces of research methodology together with theoretical knowledge and our ethnographic fieldwork on the meaning of urban space and place. The mini fieldwork project on Street Art was a great Talking Streets success. Thank you to my lecturer Yasmin for devising and teaching this, and Simon Finnis, Beth Jordan, and Kelly Moiseff for your great participation. Loved It.” Apu Samadder: April 2016

Talking Streets students against graffiti background by Stik Street Art, Bricklane, East London March 2016

Copyright © 2016 Yasmin-Hales Henao. All Rights Reserved.

Recent Comments